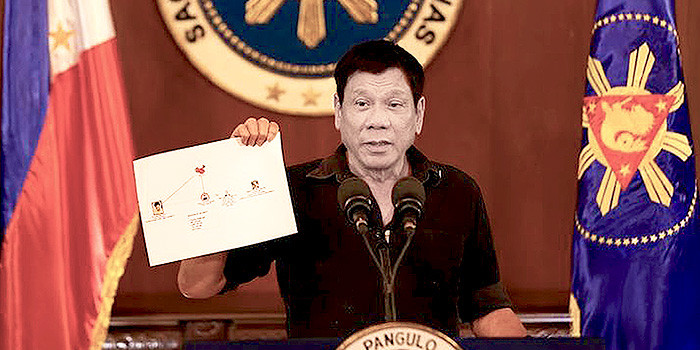

Since his inauguration on June 30, Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has been true to his campaign pledge of cracking down on drugs. He has ignored objections from within the Philippines and abroad about extrajudicial killings of supposed drug pushers and users by police and unknown assailants, which have already amounted to over a 1,700 deaths.

Why has a mounting body count and obvious violations of the rule of law and human rights failed to slow Mr Duterte’s ‘war on drugs’?

One reason is his sky-high poll rating of 91 per cent. Official statistics show crime has risen and drug use is widespread. Mr Duterte has played to a moral panic, arguing that criminality endangers the lives of people he vowed to protect.

Mr Duterte’s ability to flout fundamental principles of the rule of law is also grounded in the weakness of basic political institutions. Mr Duterte was elected with only a handful of congressional allies. But because Philippine political parties are weak he now has the support of most legislators who simply switched sides after his victory in search of presidential patronage.

Few Critics of Duterte’s War on Drugs

This has left only a few critics in office to speak out against the crackdown, particularly the separately elected vice president, Leni Robredo, and neophyte Senator Leila de Lima. Recently Mr Duterte has upped the rhetorical stakes, accusing Senator de Lima, who’s urged an investigation of the killings, of immorality and involvement in illegal drugs. Allegations the senator has vehemently denied and which led critics to once again point to Mr Duterte’s misogyny.

Mr Duterte also feels he can ignore the Philippines Supreme Court because it has been politicised, in part via his predecessor Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino’s removal of the Chief Justice, widely seen as an act of political revenge.

Several leading Catholic Bishops have voiced strong criticisms of the extrajudicial killings. But Mr Duterte revels in pointing to the hypocrisy of the Church, particularly the institution’s vast wealth and priests’ abuse of children.

Civil society groups have also been outspoken critics of the extrajudicial killings but have become fractured, with many leading members crossing over to government. On the far left, the Communist Party charge Mr Duterte for ‘upturning the criminal judicial system and denouncing people for defending human rights’. But because Mr Duterte has handed out several of their allies key cabinet positions, and because of their eagerness for a peace deal, the left’s criticism has been muted.

Mr Duterte has also kept the media off balance. During the campaign, he warned reporters not to take his outrageous statements too seriously. He also dampened criticism by pointing to reporters’ being complicit with corrupt politicians and criminals they were supposed to expose.

On the United States, Mr Duterte called US Ambassador Philip Goldberg a ‘gay son of a whore’. Mr Duterte struck a note with many Filipinos by pointing to past US double dealings as a colonial and postcolonial power in the Philippines and questioning whether the declining superpower would really back the Philippines if it came to an armed confrontation with China over competing territorial claims.

Mr Duterte has thus far skilfully outmanoeuvred his opponents by exposing their own frailties. But there are signs that he may have difficulty sustaining his violent anti-drug campaign.

The human cost of the carnage has become all too evident. There have been a number of high profile ‘mistakes’ in the killings — many clearly innocent victims. Even those murdered who did use or sell drugs have been denied any kind of due process. The Philippine Daily Inquirer’s ‘Kill List’, documenting the daily killings (recently averaging about 10 a day), points to the skewed nature of the killings: the overwhelming majority of the victims are poor and from disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

To divert attention from the criticism that the war on drugs has largely targeted the poor, the Duterte administration recently released a list of 150 police and military officials, politicians and judges accused of involvement in the drug trade. But targeting high-ranking officials carries risks of its own with the possibility that his elite enemies may regroup for a counterattack, endangering political stability.

A look at Thailand and the 2003 anti-drug crackdown by then Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra is instructive. Although the campaign lifted Thaksin’s short-run popularity, elites soon turned on him, overthrowing his government in 2006 and his sister’s government in 2014. Thai authorities are now talking of treating drug addiction as a health problem and are considering a partial decriminalisation of drugs as a more effective way of dealing with the problem.

This holds out the hope that Mr Duterte will stop or slow the extrajudicial killings. Hopefully the damage they have caused to the country’s judicial system and law enforcement is not permanent and the administration will focus on the fundamental woes of poverty and feeble political institutions that breed uncivil social behaviour.

This article was written by Ronald Holmes, a Research Scholar in the Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs at the ANU. Mark R. Thompson is director of the Southeast Asia Research Centre at the City University of Hong Kong. It first appeared on East Asia Forum under a Creative Commons license and is reproduced here with its permission.

The author will speak further on this topic at the Philippine Update Conference to be held at The ANU on 2-3 September 2016.

Related:

- Human rights group urges President Duterte to stop killings (CNN)

- Lawmakers on anti-crime fight: Follow rule of law (Philstar)

- UP Law students condemn extrajudicial killings, urge rule of law (INQUIRER.net)

East Asia Forum

It consists of an online publication and a quarterly magazine, East Asia Forum Quarterly, which aim to provide clear and original analysis from the leading minds in the region and beyond.

Latest posts by East Asia Forum (see all)

- China’s South China Sea bullying seeing increased blowback from Asean claimants – February 2, 2022

- Illusionary, delusionary or visionary? Cambodia tests living with COVID-19 – December 6, 2021

- Prioritising a Philippine–EU FTA is vital for post-pandemic recovery – July 26, 2020

- Time for Asean to stand up for itself in the South China Sea – July 25, 2020