Cambodia recorded its sharpest daily decline of COVID-19 cases when they fell from 978 to 232 between September 30 and October 1, 2021. This dramatic 76 per cent drop was due to a change in Cambodia’s approach to COVID-19 testing. By eliminating random testing of asymptomatic individuals, testing numbers only reflect COVID-19 cases that present for testing following the onset of symptoms.

This change has affected policy relating to lockdowns and border closures. After the Pchum Ben festival ended on October 7, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen announced that should COVID-19 case numbers remain low, the country would reopen.

With the sharp drop in testing, COVID-19 case numbers have remained predictably low, leading to the easing of lockdowns and the opening of borders.

On November 1, Prime Minister Hun declared Cambodia ‘fully reopened’ and that it could ‘expect crowded shops and roads’. But is this approach to ending the pandemic illusionary, delusionary or visionary?

The answer depends on whether it is time to redefine the pandemic by changing how it is measured.

Do circumstances warrant a shift in focus from infection to hospitalisation rates? The answer depends on the vaccination rate, and the capacity and quality of the healthcare system.

World leading COVID-19 vaccination rate

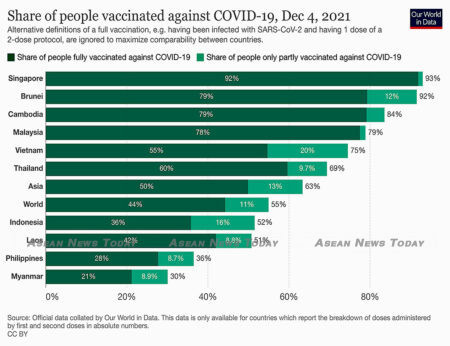

With more than 80 per cent* of its total population either partially or fully vaccinated and with third-dose “booster” shots already rolling out, Cambodia’s vaccination rate is one of the world’s highest.

It has vaccinated most children aged between 6–12 and started a vaccination programme for 5-year-olds.

Cambodia has one of the youngest populations in Asia, so extending vaccinations to these age groups is important for reaching “herd immunity”.

While adequate supplies of vaccines from China were important in achieving the vaccination outcome, Cambodia deserves credit for enabling a rapid rollout under challenging circumstances by managing the logistics efficiently.

Although the healthcare system in Cambodia is improving, its capacity is still limited.

There are only 0.7 hospital beds per 1000 people, compared to 2.6 in Vietnam** and 2.1*** in Thailand, compared with an average of 4.7 among OECD countries.

A surge in cases requiring hospitalisation could quickly overwhelm Cambodia’s healthcare system. But how will the decision to drastically reduce testing affect this risk?

It would certainly diminish the usefulness of reporting the positive infection rate. Apart from being an indicator of adequate testing in itself, accurate infection statistics could be used to monitor the outbreak and introduce pre-emptive lockdown or social distancing measures.

Risk becomes uncertainty

The Cambodian infection rate fell from 12.8 per cent of tests on May 28 to 7 per cent on June 19, presumably due to the lockdown. The World Health Organization (WHO) has suggested that rates under 10 per cent indicate adequate testing — but that rate is no longer useful when testing is confined to only those displaying symptoms.

Reopening while reducing domestic surveillance, such as testing, could backfire if emerging signs of an outbreak that could overwhelm the healthcare system are missed. This converts risk — where the probability of occurrence can be estimated — into uncertainty, where it cannot.

Instead of reducing testing to justify scrapping domestic surveillance, early warning systems should be retained, or strengthened, when exposing healthcare systems to increased risks. The return of healthcare system stresses in parts of Europe and South Korea highlight this concern.

With limited healthcare capacity Cambodia will have to rely on the efficacy of its extensive vaccination programme to protect the community.

The biggest threat to this approach is the emergence of a new variant that significantly erodes the efficacy of current vaccines in preventing severe disease.

Border closures ineffective prevention against SARS-CoV-2 variants

Although this concern underlies much of the hesitancy with opening borders in Asia, evidence suggests that border closures have failed to keep new SARS-CoV-2 variants out.

Borders are, by design, never completely closed, because that would be both impractical and unsustainable. Since borders are not completely shut, domestic safeguards need to be perfect, but are not.

Selective travel bans could only work if the time taken to determine the risks carried by new variants were drastically reduced. It took about two weeks to genetically profile the Omicron variant and declare it a variant of concern.

If it turns out to be as transmissible as feared, the bans would have come too late; if not, they were unnecessary to begin with.

Border measures will not protect against this or future SARS-CoV-2 variants, but improved domestic protocols, including testing, might.

The current state of healthcare in Cambodia is a reminder that the lives-versus-livelihoods trade-off is different in poor countries.

When fiscal resources are limited and safety nets are wanting, lives and livelihoods are often one and the same among the poor.

Poor countries must consider the lives lost or shortened by lockdowns against lives lost directly to the virus. With more than a third of GDP generated by tourism, border closures are no longer justifiable.

The switch from pandemic to endemic may prove to be visionary, even if the sudden drop in infections is largely illusionary, and changing policy based on it remains delusionary.

* Our World in Data December 5, 2021

** 2014 figure

*** 2010 figure

This article was written by Jayant Menon, a Visiting Senior Fellow at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, on East Asia Forum under a Creative Commons License and is reproduced here with its permission.

An earlier version was published here by ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute as a Fulcrum commentary.

Feature photo John Le Fevre/ photo-journ.com

Related:

- Economic fallout to challenge Cambodia’s COVID-19 success (Asean News Today)

- COVID-19: the time to act on food security is now (Asean News Today)

East Asia Forum

It consists of an online publication and a quarterly magazine, East Asia Forum Quarterly, which aim to provide clear and original analysis from the leading minds in the region and beyond.

Latest posts by East Asia Forum (see all)

- China’s South China Sea bullying seeing increased blowback from Asean claimants – February 2, 2022

- Illusionary, delusionary or visionary? Cambodia tests living with COVID-19 – December 6, 2021

- Prioritising a Philippine–EU FTA is vital for post-pandemic recovery – July 26, 2020

- Time for Asean to stand up for itself in the South China Sea – July 25, 2020