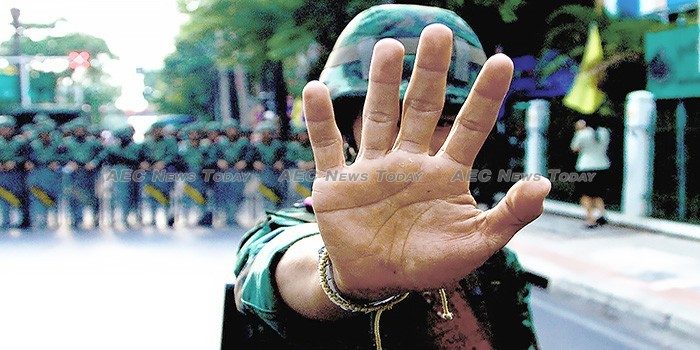

More than four years after it seized power in May 2014, Thailand’s military government appears intent on holding onto it indefinitely. Led by General Prayut Chan-o-cha, the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) has repeatedly delayed the pledged Thailand elections, currently slated for February 2019.

However, this could again be pushed back several months owing to the enforcement of laws that accompany the junta-backed 2017 constitution.

The junta will use all means available to contest and win the next Thailand election. Its efforts will be reinforced by a constitution that designates one-third of the legislative assembly to military appointments. Consequently, Thailand is likely to be under long-term military supervision.

Despite the country’s economy forecast to expand at a sub-par 4.5 per cent this year, Thai politics will remain unsettled, unbalanced, and inherently unstable. Stuck at a political standstill characterised by polarisation and conflict since 2005, Thailand risks stagnation if it cannot navigate a way out over the next two to three years.

Thailand’s trinity: military, monarchy, bureaucracy

At issue is whether the country can find a new balance between being a kingdom and a democracy.

From 1947 to 1997, the Thai economy expanded phenomenally at about 7 per cent per year. Over this nation-building period, in the thick of its Cold War fight against communist expansionism, Thailand’s political order came into place.

The regime revolves around the symbiotic military-monarchy relationship, flanked by a civilian bureaucracy fanned out across the country.

Despite elections and political parties that came and went, the trinity of military, monarchy, and bureaucracy called the shots in Thailand until it was challenged over the past two decades.

Prior to the 1997 to 1998 economic crisis Thailand’s socio-political foundations were transformed. People had more means, education, and information from media proliferation, and broader exposure to the outside world.

The rise and demise of Thaksin Shinawatra

The boom before the economic crisis culminated in unprecedented political reforms, capped by the 1997 constitution that promoted greater political transparency, accountability, and stability.

Thaksin Shinawatra, an ambitious telecommunications magnate, was uniquely positioned to capitalise on post-crisis recovery and the new post-1997 politics.

Thaksin drew upon a network of police and military classmates and associates who had accumulated new wealth from stock market growth and global finance.

Thailand’s two coups in 2006 and 2014 and a judicial move in 2008 — the three blows that ousted the Thaksin-aligned governments, including that of his sister Yingluck Shinawatra — were rear-guard actions from the old political trinity to forestall changes and upend what they saw as an upstart and a usurper.

The anti-Thaksin yellow-clad columns are beneficiaries of the former era — not ignorant of the 21st century, but insistent on entering it under their own terms.

The pro-Thaksin red shirts on the other hand, are an awakened 21st-century movement. They want to move beyond the old order as beneficiaries of Thaksin’s policy agenda.

This is the context of King Maha Vajiralongkorn Bodindradebayavarangkun’s rise after the long reign of his father, the late King Bhumibol Adulyadej. The monarch in Thailand has traditionally been considered the final arbiter and broker of power in times of crisis and debilitating impasse.

New monarchy is uncharted waters

However, that modality was specific to and personalised by King Bhumibol and his earned moral authority as a unifying and rallying symbol for the country. A new monarch in an old traditional monarchy is uncharted waters for Thailand.

If the old order trinity prevails via military-authoritarianism, underpinned by a manipulated constitution, a military-led coalition government is likely to result when the Thailand election eventually takes place.

The government would likely be spearheaded by the pro-military Pracharat Party, smaller parliamentary allies and the junta-appointed senate.

In this scenario, the political space would be more open, but ultimately the traditional trinity of institutions would be in charge.

Thaksin’s Pheu Thai Party and new groups such as Anakot Mai (Future Forward) appear set to be in opposition after the election. Constitutional rules favour smaller parties at the expense of bigger competitors.

Factions of Pheu Thai have been induced to join Pracharat, while monitoring agencies such as the election and anti-corruption commissions are dominated by junta loyalists.

The Democrat Party, which has not won an election since 1992, is now split between those in favour of the junta and others who are sceptical. This party is unlikely to lead the post-election government, although it could play a kingmaker role if it cuts a deal with the junta.

Political repression cannot be exchanged for growth

The next election, in other words, will not resolve Thailand’s structural conflict. If authoritarianism prevails, tensions will likely build towards confrontation.

Thailand’s civil society is seasoned and broad-based, while the economy is diverse, complex, and sophisticated. Political repression cannot be easily exchanged for growth and better standards of living.

Thailand will lack an attractive narrative unless and until the old guard trinity gives way to balance and compromise under a new reign.

However, the country’s political situation is likely to get worse before it can reach any kind of a new settlement.

This article was written by Thitinan Pongsudhirak, a teacher of international political economy and director in the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University in Bangkok. It previously appeared on East Asia Forum under a Creative Commons License and is reproduced here with its permission.

Related:

- Peua Thai to Prayut: ‘If you’re so popular, hold elections now’ (Asia Times)

- Thai political parties open to joining hands (The Straits Times)

- Thailand’s military junta may at last be ready to call an election (The Economist)

East Asia Forum

It consists of an online publication and a quarterly magazine, East Asia Forum Quarterly, which aim to provide clear and original analysis from the leading minds in the region and beyond.

Latest posts by East Asia Forum (see all)

- China’s South China Sea bullying seeing increased blowback from Asean claimants – February 2, 2022

- Illusionary, delusionary or visionary? Cambodia tests living with COVID-19 – December 6, 2021

- Prioritising a Philippine–EU FTA is vital for post-pandemic recovery – July 26, 2020

- Time for Asean to stand up for itself in the South China Sea – July 25, 2020